“Haters gonna hate. Hackers gonna hack.”

This attitude is reflective of the hacktivist who defaced several “.my” sites to demand that Malaysians show Bangladeshis the respect they deserve.

In his message on the defaced sites, the hacker in question, Tiger-M@te, implied some serious issues which warrant a serious look at the issue of foreign-local relations in Malaysia: the fact that many Malaysians are prejudiced against Bangladeshi workers and do not consider them equals. Tiger-M@te’s defacing of the sites is also used as evidence that Malaysians are not, in fact, “more advanced” than Bangladeshis.

My article will not touch on the treatment of migrant workers, as this has been discussed in great depth by Linda Lumayag and Angeline Loh. Instead, I’d like to focus on another equally pressing issue – that of hacktivism itself.

The question I initially hoped to answer is this: Is hacktivism good or bad? What I find, however, is that the question of hacktivism is really an ethical dilemma, and that it isn’t possible to paste a black or white label on it.

The nature of hacktivism and its intended consequences

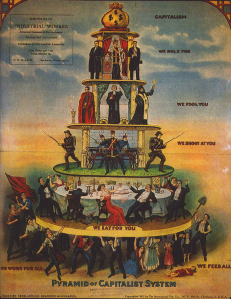

The word “hacktivism” is a portmanteau of the words hack and activism. Hacking, in this sense, is used by hackers as a tool (not dissimilar to demonstrations and protests) to achieve a political end. In short, hacktivists are people working to better society in some way – and they do so by raising awareness, boosting morale and influencing emotions in order to disrupt bureaucratic processes and inflict fear upon the misguided ruling class. These anonymous hacktivists are perfectly capable of pranking, damaging sites, and compromising confidential information; this is played very well to their advantage.

Of course, this is a representation of the people’s power on the net: when push comes to shove, the people will respond in kind and give the ruling class hell. It is an effort to reclaim power in a counter-movement.

But I find this too simplified a definition which does not truly represent the multifaceted and complex nature of hacktivism. The word activism evokes a sense of sympathy and the idea of making the world a better place, but it is in fact, somewhat misleading. The nature of hacktivism itself is equivalent to that of an equally contentious issue, that of civil disobedience.

Hacktivism as civil disobedience

In his classic essay, “Civil disobedience”, Thoreau states that it is the duty of the people to go against the rule of a morally corrupt government, even when that means violating the law. After all, “it is not too soon for honest man to rebel and revolutionise”. Thoreau himself was imprisoned as a result of his unwillingness to pay taxes. He justifies it with simple logic: if you oppose slavery, you cannot pay taxes (which are an indirect form of funds and support) to the government that condones it. People have a duty to go against unjust laws, even if it means getting incarcerated.

In equating hacktivism to civil disobedience, we can now better appreciate the problem of hacktivism. More often than not, hacktivism is illegal, and can have widespread consequences (often negative).

During his interview in 2011 about Anonymous’ Operation Malaysia, the then Minister of Information, Communication and Culture, Rais Yatim, managed to point out some accurate facts – that hacktivism is “strange” (perhaps chaotic may be a more accurate term), politically motivated, and of course, disruptive.

From the point of view of a conservative who wants everything in smooth, working order – hacktivism is terrorism. After all, the consequences can be severe. For example, the disruption of banking services may halt transactions and potentially cause large losses.

One familiar with Gandhi’s methods of resistance might initially be tempted to draw a parallel between his tactics and the hacktivists’. But the core difference lies in the activity.

Hacktivism is by no means passive, and usually is an “eye-for-an-eye” response. Hacktivists take an active stance in creating chaos and inflicting fear, which is the complete opposite of Gandhi’s and Shelley’s passive resistance methods of shaming, love and pride. This is especially notable in anarchist coalition Anonymous’s slogan: “We are Anonymous. We are Legion. We do not forgive. We do not forget.”

Should we support hacktivists?

My own observations note that hacktivism is by nature neither right nor wrong. In considering the merits of hacktivism, we must look into each movement as unique, isolated cases (unless, of course a similar hacker team claims responsibility). What many observers tend to do is to lump all hacktivist movements under one umbrella, usually Anonymous. But the individuals responsible are likely to be different people who come from different backgrounds and with different backing philosophies.

That aside, regardless of the intended consequences and its moral position, hacktivism is still a crime. In the US, hacktivist Aaron Swartz was faced with upwards of 30 years of prison and US$1m in fines because he downloaded millions of academic journals from pay-to-view database JSTOR in order to make them open access. Even after he had returned all the downloaded files to JSTOR and the settlement was made between both parties, the US federal government continued to press charges – and Aaron Swartz eventually committed suicide.

One has to wonder, then, is the consequence really worth the legal trouble?

Hacktivists: Heroes, anti-heroes or villains?

In another instance, hacktivists hacked into Sarah Palin’s email to obtain and disclose any potentially illegal or scandalous content. Is this justifiable disobedience? Dissatisfaction towards Sarah Palin is really because of people’s negative impression towards her perceived lack of intelligence. Those who read Mill may identify this as none other than “the tyranny of the masses”, where the public (through the control of opinion and emotions) creates a form of hegemony where people who are not part of the in-group are punished socially or even physically.

Thus, we need to reconsider our ethical and philosophical positions. Where do we draw the line between being merely civilly disobedient and a terrorist? How far should we go in advocating radical views and acts?

As technology advances and our reliance on it increases, hacktivism’s effectiveness (in pushing a message across) and its accompanying disasters will become more apparent. Before that happens, we need to question our own sense of morality and judge each issue more rationally.

But a point to keep in mind is that, while the rational citizen is often considered the ideal citizen, as hacktivists may say, sometimes, an emotional answer can also work as a perfectly rational solution.

*This article was first published in Aliran:

http://aliran.com/14544.html